Ask Thucydides!

(“The Baker Street Irregulars’ ‘Thucydides’ whose Archival Series

has set the standard for any literary society’s history” -- Wiggins)

Got a question about this website?

or BSI history in general?

Send it to AskThucydides@gmail.com

Chris Redmond (“Billy,” BSI) asks:

I thought it must be in Irregular Crises, but I am not finding it there. I mean the quotation from the bar bill at some long-ago BSI Dinner, listing the number of whiskies, gins, and scotches consumed, and "1 beer"? If this rings a bell with you, I'd greatly appreciate the reference.

It’s from Irregular Proceedings of the Mid ‘Forties, p. 261:

Edgar W. Smith to Christopher Morley, January 14, 1946:

. . . you will be interested in the found-fact that the liquor consumption on Friday was 96 cocktails, 243 scotches, 98 ryes and 2 beers. Financially, I showed a profit on the evening of $22, which I have posted against past deficits without a qualm.

Morley back to Smith, January 17, 1946:

Official pronouncement, by the Gasogene-and-Tantalus, on yr memo re the found-fact of liquor consumption at the dinner last week:--

Hail to you, Edgar, our liege duniwassal,

(A word that I somehow remember from Scott)

Equally shrewd as cashier or apostle;

Always observing Who’s Who and What’s What.

Baker Street, once a year, calls each Irregular

To dine at prix fixe and tres cher table d’hote:

Walbridge, alas, incessantly jugular,

Makes a canal of what’s only a throat.

But that’s forgotten. Hail, Man with the Watches!

Now for the first time he’s not in arrears ---

“96 cocktails, 243 Scotches,

98 ryes -- and a couple of beers!”

Chris is planning one of his very infrequent trips to New York for next January’s BSI weekend, and I think I know what aspect of it is on his mind.

Nicholas Utechin in Oxford asks:

I’ve just finished re-reading Irregular Crises of the Late ‘Forties which, of course, had to end just as the BSJ was about to be relaunched. I thus would be fascinated to know one or two facts about the birth of the New Series BSJ. I ask because my Vol. 1 Nos. 1-2 are, sadly, ‘Reproduction Issues.’ I presume that Edgar W. Smith understandably only had printed . . . what . . . 200 copies of the first two, and then the response was positive enough to go for reprints? Did he do that just for Nos. 1 and 2? I’ve love to know what the quantities and history were.

Edgar Smith provided some of the desired information himself in a “Special Notice to ‘Old-Time’ Irregulars” that was included with some copies of the July 1951 issue sent out. Anxious to avoid another failure through lack of support, he was appealing to 60 BSI “old-timers” (“in order to spread the clerical load, and to facilitate the voluntary work by which alone the Journal can keep going”), to renew their subscriptions for 1952 right away without waiting for the renewal form that would accompany the October issue, the final one of the year.

(And perhaps also, he suggested, to give gift subscriptions to one or two of their friends “who might, by receiving this repository of the wisdom of the ages, be converted to full-fledged Irregularity.”)

The press runs for each issue were already growing, he told the 60 graybeards: “Only 200 copies of Volume 1, Number 1 were printed, and 250 copies of Volume 1, Number 2. This current July issue has been stepped up to 300 copies, and 400 are in prospect for October.”

Nos. 1 and 2 “reproduction issues” had to wait until the NS BSJ seemed securely on its feet, its subscriber base grown to a safe point and new subscribers seeking copies of the first two Numbers. Edgar was forever an optimist. The BSJ’s circulation wasn’t the deep dark secret that it is today, but it will take further research to uncover just when those “reproduction issues” were produced.

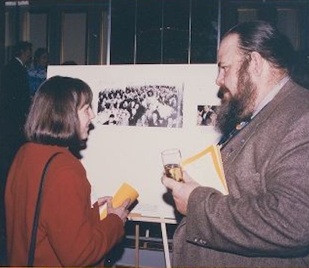

John F. Farrell was “The Tiger of San Pedro” in the BSI since 1981. A prolific music and theater critic in Los Angeles area newspapers and magazines, he died in May, seated at his keyboard writing a review when the fatal heart attack came. This is John below, at the 1993 BSI weekend in New York, with my wife Susan Jewell.

John was like an enormous Mountain Man of the Arts, a man of tremendous enthusiasms. He will be greatly missed by his readers in the L.A. area, and by all Irregulars who knew him. He was only 63 and one of a kind.

Almost precisely a year ago, during my website’s Great Hiatus, I received a BSI history question from John, so here it is, and Thucydides’ answer.

BSI Archive; photo by Dorothy Stix, BSI.

I recently thought maybe I could buy a copy of the same book by Grillparzer that Morley used for the original Irregulars, and I remembered Tom Stix once telling me that he owned the book, but didn’t want to give it to the BSI, instead to pass it on to someone who would care for it. I contacted Mike Whelan about it: I thought he would know enough about it that I could get another copy. The book, as I understood it, wasn’t rare and might be available.

Mike Whelan wrote me saying that Tom Stix never had possession of the Grillparzer Book, and that there are no copies extant because it was a blank book into which club members wrote short commentaries. Can you tell me what you know about the book? I’m sure Tom said he had it and did not want to pass it on to the BSI, and even more sure it wasn’t a “blank” book: why was it called the Grillparzer Book if it was blank? I still want to get a copy, if I can find out the publisher and etc. I am sure it is out there.

Christopher Morley’s Grillparzer Book went from Morley to W.S. “Bill” Hall, from him to Julian Wolff, and from Julian to George Fletcher.

And you’re right, it’s not a blank book. It’s Gustav Pollak’s Franz Grillparzer and the Austrian Drama (Dodd Mead & Co., 1907), a copy of which Morley found in a used book shop and brought to a Three Hours for Lunch Club lunch one day in 1930. It’s not terribly rare, and you can probably obtain a copy at a reasonable price at abebooks.com.

(I have a copy myself, given to me by the other members of The Half-Pay Club of Washington D.C., a monthly lunch I started in the late 1980s, when I was leaving the government in 2006 and relocating to Chicago -- after they’d given it the Morley treatment, all of them writing commentaries of our association in it on various pages.)

George Fletcher has an entire chapter describing Morley’s Grillparzer Book and its history in my BSI Archival History volume Irregular Memories of the ’Thirties. George is “The Cardboard Box,” 1969. He received the Two-Shilling Award in 1983 for the immense help he gave Julian Wolff with the BSJ over many years, and was its actual publisher a number of years when he ran Fordham University Press. George went on to be Astor Curator of Printed Books and Bindings at the Pierpont Morgan Library, later Director of Special Collections at the New York Public Library. He is a leading member of the Grolier Club today as a rare books & manuscripts authority, and a bibliophile whose exhibitions there and elsewhere are glowingly reviewed in the New York Times.

“Say, Thucydides, old egg,” says Susan Dahlinger, rather disrespectfully to an elder of my antiquity, “several graphs below your inquiry re the Julian Wolff signature [next below], you mentioned that Conan Doyle’s “dreadful son” Adrian remarked that his father didn’t have a typewriter. That’s surely the carriage of an Underwood typewriter peeking out behind Arthur Conan Doyle’s left arm as he works at his desk on the cover of Daniel Stashower’s Teller of Tales.”

Never used a typewriter, I think I said Adrian claimed (along with knowing his father better than anyone else living or dead). But Conan Doyle had used one occasionally for decades before Adrian was even born, stating at early as September 28, 1891, in a typewritten letter to his mother Dan Stashower and I included in our book Arthur Conan Doyle: A Life in Letters, “It is so long since I have had any practise with my type-writer that I must really have a little now at your expense. It has however been a very useful investment to me . . . .” And while I couldn’t say what brand it is, that does appear to be a typewriter behind him, much later in life, in the cover photograph of Dan’s Teller of Tales.

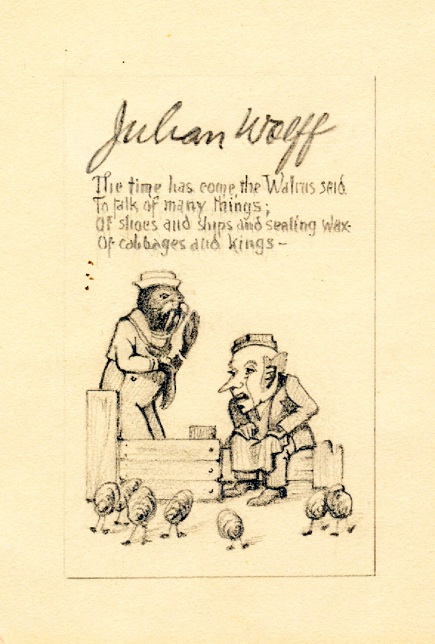

Julian Wolff & Lewis Carroll?

Peter Blau asked George Fletcher: “Someone asked about this bookplate . . . the signature looks authentic . . . do you think the artwork’s Julian’s? Was he interested in Lewis Carroll?” George replied: “Either it’s news to me, or I’ve

As Peter says, “it’s hard to imagine anyone forging Julian’s signature to make some money, since he signed just about everything he sent to anyone . . . It was the possible Lewis Carroll connection that intrigued me, since I wasn’t aware of that as one of his interests, but as you say, one never knows.”

Can any reader shed light on this? Please let Thucydides know at the email address at the top of the column.

THADDEUS HOLT, noticing a discussion way below of the 1971 BSI dinner at The Players -- the second and as far as both club and BSI were concerned the last there -- has this to say:

Browsing, I saw the discussion of the 1971 dinner at The Players. I was there, but I don't remember that much about it. Based on the description of the bartending, it was a case of if you can remember it you weren't there.

From the earlier discussion (scroll down for the entire thing):

I asked Jim Saunders and George Fletcher for their memories. Jim said: “I was at the dinner but my memory of this incident is very vague. I remember Alfred Drake as being rather obnoxious. I think he was drunk. George Fletcher and I had a drink at the bar afterward but they wouldn’t let us pay. They put everything on Julian’s membership account. Julian had quite big bill, I understand.”

George suggests that everyone there was drunk, and that was part of the problem:

My recollection is about the same as Jim’s, and along the following lines, although uncertain after all these years. Someone (don’t remember who it was) who fancied himself a bit of a conjuror was at the head table, which included Alfred Drake as then-president of The Players, and seated next to Drake. This Irregular’s shtick (excuse me, “paper”) included, and ended with, igniting a bit of flash paper that erupted and fell from his hand onto the tablecloth, thus landing in Drake’s immediate proximity. Much stamping and huffing. Drake was there in his Players capacity (dragging him away from a perpetual card game somewhere in the distant upper reaches of the building), was or wasn’t rather full of himself, and/or was annoyed at having to spend a good part of his evening with this crowd of outsiders, and probably drinking as much as everyone, especially the bartenders with their rolling bars boozing it up.

Ah yes, the tab. Julian told me later that the bar bill was of the magnitude of treble the food bill. Thing was, the bartenders, of whom there were several, strategically located around the rooms, were pouring generously, including for themselves, encouraging BSIs to put down their partially consumed glasses and get fresh ones -- and soon lost the ability to check off accurate numbers of drinks served. I recall one bartender as being just this side of falling-down drunk. Many BSIs were only too happy to get a fresh one when the old ice cubes had dwindled or the mixer had lost its fizz, or some combination thereof, and I recall the vast array of partially consumed drinks sitting all over the place. Julian, as member-host, of course had the entire debit levied against him. This was the last dinner at The Players; after that, the Regency with its expensive (for the time) chits for drinks, and no nonsense about it. The bar tab at The Players was a main incentive for finding accommodations at the Regency.

JOHN LEHMAN BSI ASKS:

Did you catch Page 18: Lewis Carroll's typewriter?

I had not, and this is most interesting. Both for its own sake, and because it suggests what the typewriter that Conan Doyle owned in the early 1890s may have been like. His dreadful son Adrian swore that his father never owned or used one, but in fact Conan Doyle mentions having one in letters written from South Norwood, though it appears his sister Connie, living there at the time, used it mostly to prepare replies to correspondence he’d received. One of the letters, to his mother dated September 28, 1891, is on p. 295 of my Arthur Conan Doyle: A Life in Letters: “It is so long since I have had any practise with my type-writer that I must really have a little now at your expense. It has however been a very useful investment to me, for Connie often does as many as six or seven letters a day for me with it, and very well indeed she does them. In this way a great deal of work is taken off my shoulders, and I am left free for other purposes.”

MICHAEL DIRDA WONDERS:

I’m writing about A.J.A. Symons — author of The Quest for Corvo — and am thus reading his brother Julian’s biography of him. At one point, A.J.A. joins Ye Sette of Odd Volumes — this would be in the mid 1920s — and Julian Symons mentions some of the rules of this book-collectors club. Rule XVI is “There shall be no Rule XVI.” The members of the Sette also take on whimsical names: “Each Odd Volume was expected to assume a title symbolical of his occupation or inclination, and was known by this denomination at meetings of the Settte. Thus Williamson was Brother Horologer, Ralph Straus Brother Scribbler. . . .”

Did you know this? Could the BSI have taken Ye Sette of Odd Volumes as a partial model for itself?

STEVE ROTHMAN, BSJ editor and bookman, comments:

Nice exchange. A rather large archive of the Sette is at the Clark. They wrote about it in a recentish newsletter. Mr Google supplies a link www.c1718cs.ucla.edu/content/nwsltr/newsletter54.pdf

The report at Steve’s link on Ye Sette of Odd Volumes makes interesting reading even if we fail to find a connection to the BSI. (Speaking as both a University of Southern Cal alumnus and a Holmesian, a good reason to visit UCLA is always welcome!)

_________________________

I know about Boston’s Club of Odd Volumes, as I’m sure you do, but this English outfit is new to me. Elmer Davis’s Constitution & Buy-Laws, as we now know, originated in one he’d written for an entirely different uproarious club in 1915 — see Ch. 4, “The Friendly Sons of St. Vitus,” in my 2009 BSI Archival History volume “Certain Rites, and Also Certain Duties” — but he ended that 1915 document with “Article VI shall be the last article of the Constitution.” (I’m also reminded of Rule 6 of the constitution of The Coffee House Club where our BSI Special Meeting takes place in January: “There Shall Be No Rules.”)

It’s possible Christopher Morley, deep-dyed bookman, was aware of Ye Sette of Odd Volumes. BSI investitures, however, arose in 1944 with Edgar W. Smith, who drew upon a tradition of The Five Orange Pips. Please let me hear any more you discover. I’d be particularly interested if one of its members in the 1920s was Stanley Morison, because it was Morley’s chance meeting with him in New York in 1926, that revived Morley’s long-dormant boyhood enthusiasm for Sherlock Holmes.

Mike replies: Stanley Morison was certainly part of A.J.A. Symons’ orbit. The Fleuron, which Morison edited, printed Symons’s essay on Fine Printing, and Morison comes up in Symons’ retrospective essay on the Nonesuch Press, which was founded by their mutual friend Francis Meynell. Symons himself started The First Editions Club and I suspect that Morison would have joined that. Being a clubbable man, Symons also founded — with Andre Simon — The Wine and Food Society.

This suggests an interesting possibility. In his “Bowling Green” column in the May 1, 1926, Saturday Review of Literature, Morley said:

The other day I had the good fortune to meet a famous English printer who is visiting in this country; and instead of talking about Plantin and Caslon and Bruce Rogers we found ourselves, I don’t know just how, embarked on a mutual questionnaire of famous incidents in the life of Sherlock Holmes. “What was the name of the doctor in ‘The Speckled Band’?” he would ask; and I would counter with “Which mystery was it that was solved by the ash of a Trichinopoly cigar?” “Who was the fellow who had the orange pips set on him” he cried; and I, “What was the adventure they cleaned up early enough in the evening to go and hear a concert at Queen’s Hall?” Our hosts were startled to find us, so passionately happy in this pastime, which might well have gone on for hours. We concluded that since Sir Arthur is writing some new Holmeses, the real thing to do would be a book all about Mycroft Holmes, the mysterious older brother, in which Sherlock would appear only as an amateurish and promising youngster.”

How I wish there’d been a garrulous eye-witness to that meeting of Morley and Morison in New York in 1926!

PORLOCK ASKS:

Last January, at the BSI dinner at the Yale Club, more Irregulars than just me were surprised by Mike Whelan's “excommunication” remarks which arose from his wife Mary Ann Bradley’s Xmas Annual about Lenore Glen Offord. I jotted them down: “Edgar [W. Smith] excommunicated people by giving their investiture to someone else . . . silent excommunication . . . how subtle . . . more on this later.” What’s going on here?

I wish he’d consulted me beforehand. The notion’s wrong, and the tip-off should have been the misapprehension’s source — S. Tupper Bigelow’s letter to Poul Anderson in W. T. Rabe’s Who’s Who & What’s What, the 1962 edition. Bigelow was scrambling to apologize for casting doubt on Lee Offord’s investiture (as “The Old Russian Woman,” 1958) genuineness or validity. He was wrong not only about that, but about the excommunication business, talking through his hat in his embarrassment. (Further details here.)

Here’s the analysis:

Edgar Smith gave the same investiture to more than one person on fifteen occasions: The Abbey Grange; The Beryl Coronet, The Bruce-Partington Plans; A Case of Identity; The Dancing Men; The Five Orange Pips, The Golden Pince-Nez; The Greek Interpreter; The Man with the Twisted Lip; The Old Russian Woman; Silver Blaze; The Three Gables; The Valley of Fear; Vamberry the Wine Merchant; and The Veiled Lodger.

In five cases, the second time he conferred an investiture, the previous holder had died:

Abbey Grange: Fulton Oursler, 1950, d. 1952; C. Milton Lang, ’53.

Bruce-Partington Plans: George Macy, 1951, d. 1956; E. W. McDiarmid, ’57.

Case of Identity: Elmer Davis, 1949, d. 1958; A. D. Henriksen, ’59.

Dancing Men: Fletcher Pratt, 1949, d. 1956; Thomas McDade, ’57.

Valley of Fear: H.W. Bell, 1945, d. 1948; Anthony Boucher, ’49.

In seven cases, the first holder was still living:

Beryl Coronet: Ben Abramson, 1949 (d. 1955); Richard Horace Hoffman, ’52.

Five Orange Pips: Rolfe Boswell, 1951 (d. 1968); S. Tupper Bigelow, ’59.

Golden Pince-Nez: David Randall, 1951 (d. 1975); Ernest Bloomfield Zeisler, ’59.

Greek Interpreter: Rufus Tucker, 1944 (d. 1972); Morris Rosenblum, ’52.

Man w/ Twisted Lip: Belden Wigglesworth, 1944 (d. 1977); Edward Bartlett, ’52.

Vamberry the Wine Merchant: Tony Montag, 1954 (living); Dean Dickensheet, ’56.

Veiled Lodger: Isaac George in 1951 (d. 1963); E. T. Guymon Jr., ’58.

And there are 2 other anomalous cases of duplication:

The Old Russian Woman: Anatole Chujoy in 1955 (d. 1969), and I wonder why that one, given other Russian references in the Canon Smith could have chosen (Chujoy was born in Riga [Latvia], mentioned by name in SIGN, but Smith may not have known where Chujoy was born); then Lee Offord, 1958, who lived on Russian Hill in San Francisco — Tupper Bigelow wanted to deny that a woman had been knowingly invested, and Poul Anderson was ticked off by this;

Silver Blaze, three times by Smith: Roland Hammond, 1944 (d. 1957): then Joe Palmer, 1953 (died later that year); and Allison Stern, 1959 (with Hammond dead by then too).

Now Smith might have been peeved with Ben Abramson, given the OS BSJ’s collapse, but I doubt he was “excommunicating” him in giving Hoffman the same investiture in ’52: Smith was a benign personality never given to nastiness even in exasperation, something clear from the many score letters of his in my Archival Histories. As many including Mike Whelan have said, the best and wisest man the BSI has ever known.

And then, Edgar Smith excommunicating the likes of David Randall, Rufus Tucker (Smith’s colleague at GM), Rolfe Boswell, or Belden Wigglesworth? All it takes is to know the notion’s absurd is to look up what men Smith supposedly excommunicated. But Bigelow had only been invested in 1959, hadn’t known Smith long or well, was outside the mainstream of the BSI, and looking for a reason to explain his receiving an investiture someone else still in the ranks had.

It looks like Smith didn’t keep track of investitures already awarded as closely as he should have, for all that he was Organization Man for the BSI. As a matter of fact I’ve never come across a working list of investitures and holders by him, and wondered why. I also note that over half his duplicates occurred after he’d retired from GM in 1954, and losing his Irregular secretarial support likely had something to do with it. The first comprehensive if imperfect list of investitures and holders I know of is one by C. R. Andrew in 1960, when Smith, alas, was dead or soon to be.

But even in 1985, when Julian Wolff had Peter Blau’s excellent lists to work from, and Tony Montag and Dean Dickensheet were both alive, he conferred Vamberry the Wine Merchant a third time, on Arthur Liebman. But I’m pretty sure Julian wasn’t excommunicating Irregulars either.

ANSWER FROM DR. RICHARD SVEUM TO WARREN RANDALL’S QUESTION BELOW:

Dear Thucydides,

I have been asked for a convincing explanation of Msgr. Knox’s elementary error in Trevor’s Christian name. I can point out that in The Baker Street Journal 2010 Christmas Annual Nicholas Utechin, BSI names Percy Mitchell as a member of the Gryphon Club who first heard the paper on March 13, 1911. I propose that Percy was secretly keeping a dog in Trinity College, Oxford and Knox knew and substituted his Christian name in place of Victor. Sadly Percy was killed in action on November 6, 1917. Essays in Satire came out in 1928 and by that time Knox kept the substitution in his memory. It took one hundred years until Warren Randall detected this literary puzzle.

I appreciate the attempt by my opponent at August’s Great Debate at Minnesota over the Sherlockian insignificance of Fr. Ronald Knox, to explain away such an elementary (let us say, fundamental) mistake on Knox’s part, but I’m reminded, a bit sadly, of the famous exchange between Dr. Mortimer (another doctor given to supernatural explanations) and Sherlock Holmes in The Hound of the Baskervilles: “Do you not find it interesting?” -- “To a collector of fairy-tales.” I think we must conclude that Ronald Knox did not know the Canon well enough in 1911 (even though there was then less of it to know) to get Victor Trevor’s name right, and did not bother to review his 1911 text with this and its other mistakes when he slapped it into his collection of other writings, Essays in Satire, in 1928.

While I agree it took one hundred years for the mistake to be remarked upon, by Warren R. who not only sees but observes, I think it does indicate what I have been saying, Dr. S., that not many people were ever reading Fr. Knox’s paper, let alone paying much or close attention to it.

WARREN RANDALL writes: “I am not sure if this is a suitable inquiry for Thucydides, but I am curious if anyone has commented on these items in Ronald Knox’s “Studies in the Literature of Sherlock Holmes,” in which he says:

“The ‘Gloria Scott’ further represents Percy Trevor’s bull-dog as having bitten Holmes on his way down to Chapel, which is clearly untrue, since dogs are not allowed within the gates at either university”

and

“One of his friends was Percy Trevor, son of an ex-convict, who had made his money in the Australian goldfields; another Reginald Musgrave, whose ancestors went back to the Conquest – quite the last word in aristocracy”.

“I have not found any commentary on the substitution of ‘Percy’ for ‘Victor.’ Old Dad is only identified as Trevor Senior, while Percy is the first name of three individuals in other cases.”

An excellent question, Warren. Reading Father Knox’s essay as seldom as I do, being more concerned with the history of Baker Street Irregularity than its side-paths and dead ends, I don’t know that I’m the best one to pronounce upon the scholarly shortcomings of his text. The great S. C. Roberts did, of course, in his 1929 essay A Note on the Watson Problem, but I am far from home and without my copy to consult, to see if he had something to say about it. Let us ask the learned Professor Sveum, the well-known Knox apologist and my opponent at August’s debate in Minneaspolis, if is acquainted with this mistake of Father Knox’s on such an elementary manner, and what he thinks a convincing explanation could be.

[February 13, 2011]

Return to the Welcome page.

BOB HESS asks about “the BSI stock certificates - their history, how long they were issued, and approximately how many were issued.”

Edgar W. Smith started talking to Christopher Morley about incorporating the BSI sometime the summer of 1947, both to create a lucrative publishing program (they thought), and to manage takeover of the BSJ if Ben Abramson’s publishing of it collapsed (as it did in 1949). That November they acted, with Vincent Starrett brought in as the third required incorporator. First announcement of it came at the January 1948 “committee-in-camera” dinner (“monosyllabically,” reported Irregular Bob Harris to Russell McLauchlin back in Detroit), and then in Smith’s minutes of that dinner. Smith discussed it at more length in the April 1948 BSJ.

The first three stock certificates were issued in January 1948 to Morley, Smith and Starrett. Starrett’s is pictured on p. 124 of Irregular Crises of the Late ’Forties. 100 shares had been authorized; Morley received 23, Starrett 5, but I don’t know how many for Smith. Morley and Smith had ideas about other likely candidates, but a lot of the men they had in mind hung onto their money instead, especially as Smith wanted $250 a share. By April 1948, there were six stockholders, the next three being Frank Morley, Richard W. Clarke, founder of The Five Orange Pips, and Carl Anderson of The Sons of the Copper Beeches. That September, California mystery collector E. T. “Ned” Guymon Jr. became a stockholder. (See my Disjecta Membra voume for the Smith-Guymon correspondence.)

Miriam “Dee” Alexander, Smith’s secretary at GM Overseas Operations at the time, and serving as Secretary-Treasurer of the BSI, Inc., had already received a share as a gift in recognition of her unpaid service. Others were not pounding at the BSI, Inc.’s door, especially when its first publishing venture, the BSI edition of The Adventure of the Blue Carbuncle, was a commercial flop. (The unreality of Smith’s and Morley’s thinking is indicated by Morley’s notion at the beginning of the project that the Literary Guild alone would take 400,000 copies of the book.)

By May 1949, stockholders numbered eleven, including now William S. Hall, Ben Abramson (I suspect without paying for his share or shares), and Julian Wolff. By January 1950, there were two additional stockholders, for a total of thirteen holding a total of 65 shares, but I am confident that both received their shares for free too. One was Christopher Morley’s dogsbody Louis Greenfield, acting as unpaid Business Agent for the BSI Inc., who probably never had $250 at one time in his life. (See ch. 6 of the Late ’Forties volume). The second was Jacques R. Smith, Edgar Smith’s stepson who’d taken over the printing of the OS BSJ, and found it very hard to get paid by the failing Ben Abramson.

I can’t say now whether Smith succeeded in unloading any more shares to any additional stockholders in the 1950s, but if he did, it would have been as a purely charitable act on the part of the new stockholders, because it was clear by then that the BSI Inc. was a financial black-hole.

Names of stockholders are taken from the periodic financial reports of the BSI Inc. in my ’Late Forties and Disjecta Membra volumes. Additional data about the 1950s would be very welcome. The BSI Inc. was still active when Edgar W. Smith died in September 1960, and apparently posed an administrative burden without financial reward for his sons.

[January 17, 2011]

Return to the Welcome page.

WARREN RANDALL: Was Manfred Lee an invested BSI? The only Lee I can find connected to the BSI is Gypsy Rose in 1943.

Manfred Lee, half of the pair of cousins who were the mystery-writing team of Ellery Queen starting in the 1920s, was not a Baker Street Irregular, though he did attend the annual dinner in 1946. His cousin Frederic Dannay first attended it in 1942, and became part of the BSI for the rest of his long life (dying in 1982), and was invested as “The Dying Detective” in 1950. The best authority on the life and crimes of Ellery Queen’s two halves is Mike (Francis M.) Nevins’ book Royal Bloodline: Ellery Queen, Author and Detective, published by Bowling Green State University Press in 1974.

[December 12, 2010]

Return to the Welcome page.

ROBERT KATZ: I recollect hearing that the BSI once met at the Players Club and the speaker (possibly Leslie Marshall) ended his presentation by igniting a piece of flash paper, as used by professional magicians. I think the noted actor Alfred Drake was sitting next to the speaker and was, needless to say, quite startled by this. Do I have the basic story correct? What can you tell us about this event?

More on this matter:

Julian Wolff did not keep BSI dinner minutes the way Edgar W. Smith did from 1940 through 1960, alas. His March 1971 BSJ report of that January’s dinner (which was the second at The Players) follows, along with conclusions of mine drawn from it:

The Irregulars’ annual dinner was held at The Players on January and was attended by 100 thirsty enthusiasts. Especially notable among those present were Alfred Drake, President of The Players; Brooks Atkinson, the greatest and most scholarly of all critics; Fred Dannay, Investitured Irregular and half of the Ellery Queen team; and the Chaplain of the Irregulars, our own non-conformist clergyman, Rev. Leslie Marshall (“A Scandal in Bohemia”), who returned to the fold after many years’ absence.

It was truly a great evening from beginning — the toast to the woman, Dorothy Stix (Mrs. Thomas L. Stix, Jr.), by Bill Jenkins — to end — the reports of the Scion Societies, followed by the usual informal discussions.

Of course, all of our customs were strictly observed, and the Conanical and Irregular toasts were drunk. The Constitution and Buy—Laws, as well as the Musgrave Ritual and Sherlock Holmes’s Prayer, were read, and the Sherlockian songs of Jim and Bruce Montgomery were played and enjoyed. Greetings from individual Irregulars and Sherlockian societies in this country and abroad were read; newcomers were introduced; and we stood on the terrace to have our last quiet talk with those Irregulars who had broken from the ranks during the past year. Nor must we omit to mention those elegant keepsakes that we received through the courtesy of several Irregulars. The one from Lew Feldman(see Inventory)was most magnificent, and Fred Dannay generously supplied each of us with the Feb. EQMM, containing Michael Harrison’s masterpiece. Deserving members were honoured, and unusually good talks were heard. These were delivered by Alfred Drake, whose address revealed him to be a real Sherlockian scholar; Thomas L. Stix, who spoke of the close relationship between The Players and the Irregulars; Rev. Leslie Marshall, who showed us that the stage had lost a fine actor when he entered the ministry; Will Oursler, who demonstrated his great ability as a linguist far beyond our capabilities to comprehend; and John Bennett Shaw, who delivered a most amusing talk in the modern style, showing evidence of much research and truly specialised knowledge, but, unfortunately, unpublishable.

Julians’s report is tactfully elliptical on several points. However close the relationship between the BSI and The Players may have been, the following year saw the BSI convene at the Regency Hotel’s far less atmospheric banquet room instead, and things were never quite the same again for the annual dinner. That and his sly reference to “100 thirsty enthusiasts” bear out what Jim Saunders and George Fletcher recall below. It was this year that Leslie Marshall returned to the dinner and presented (I presume) his brief paper “A Trifle Trying” that appears elsewhere in that same issue; and given Julian’s straight-faced allusion to the Rev. Marshall’s showmanship, the flash paper would seem likely his, as Bob Katz was suggesting in his question. At any rate, that will be my working assumption unless and until evidence to the contrary surfaces.

[September 15, 2010]

Return to the Welcome page.

_______________________

It was a long time ago, 1971: the second dinner at The Players, I believe, falling beyond the scope of my Archival Histories but before my first annual dinner at the Regency Hotel (the second there) in 1973. So I asked Jim Saunders (“The Beryl Coronet”) and George Fletcher (“The Cardboard Box”), both invested in 1969, for their memories. Jim said: “I was at the dinner but my memory of this incident is very vague. I remember Alfred Drake as being rather obnoxious. I think he was drunk. George Fletcher and I had a drink at the bar afterward but they wouldn’t let us pay. They put everything on Julian’s membership account. Julian had quite big bill, I understand.”

George suggests that everyone there was drunk, and that that was part of the problem:

My recollection is about the same as Jim’s, and along the following lines, although uncertain after all these years. Someone (don’t remember who it was) who fancied himself a bit of a conjuror was at the head table, which included Alfred Drake as then-president of The Players, and seated next to Drake. This Irregular’s shtick (excuse me, “paper”) included, and ended with, igniting a bit of flash paper that erupted and fell from his hand onto the tablecloth, thus landing in Drake’s immediate proximity. Much stamping and huffing. Drake was there in his Players capacity (dragging him away from a perpetual card game somewhere in the distant upper reaches of the building), was or wasn’t rather full of himself, and/or was annoyed at having to spend a good part of his evening with this crowd of outsiders, and probably drinking as much as everyone, especially the bartenders with their rolling bars boozing it up.

Ah yes, the tab. Julian told me later that the bar bill was of the magnitude of treble the food bill. Thing was, the bartenders, of whom there were several, strategically located around the rooms, were pouring generously, including for themselves, encouraging BSIs to put down their partially consumed glasses and get fresh ones -- and soon lost the ability to check off accurate numbers of drinks served. I recall one bartender as being just this side of falling-down drunk. Many BSIs were only too happy to get a fresh one when the old ice cubes had dwindled or the mixer had lost its fizz, or some combination thereof, and I recall the vast array of partially consumed drinks sitting all over the place. Julian, as member-host, of course had the entire debit levied against him. This was, I believe, the last (second and last?) dinner at The Players; after that, the Regency with its expensive (for the time) chits for drinks, and no nonsense about it. The bar tab at The Players was a main incentive for finding accommodations at the Regency.

[September 13, 2010]

Return to the Welcome page.

BRAD KEEFAUVER (“Winwood Reade”): In listing his “academic distinctions” in his Christmas annuals, James Montgomery lists “I.S. denotes Award of the Irregular Shilling” and “B.S.I. denotes The Baker Street Irregulars” as two separate items. Was this a reference to a pre-Shilling BSI and a post-Shilling BSI?

Peter Blau, the BSI’s Recorder of Investitures, weighs in (9/12/2010):

With regard to Jim Montgomery, and the difference between membership in the BSI and the Irregular Shilling [see below], I don’t think we disagree . . . of course the real problem is that it’s difficult now to know what labels meant then . . . there are people today who say they are members of the BSI, assuming that attendance at an annual dinner is sufficient, or even being a member of a scion society . . . and there certainly were people who were indeed members of the BSI in the 1930s and early 1940s, because the society existed, and met, although I don’t think anyone cared, really, at least until the Trilogy Dinner, after which it was proposed that there be some sort of official recognition of membership.

And that was the Irregular Shilling and Investiture . . . and when I created my list, I decided it would be a list of Investitured Irregulars because there are records and thus evidence, of which there isn’t much for earlier years.

Roosevelt and Rathbone and Bruce received membership certificates, but so far as I know never Shillings nor Investitures . . . Woollcott was stated to be an Irregular by Smith . . . and there were people who were members in the 1940s and 1950s who seem never to have bothered to request a Shilling and Investiture . . . I just figured that there was no way to define membership clearly for all those folks, and avoided doing so.

I’m reminded of the distinction that once was made between Irregular and irregular, but I don’t recall who started it . . . Smith or Abramson or Rabe.*

It’s the same with my list of Sherlockian societies, which does not distinguish in any way between societies that are scions and those that are not . . . not only is it impossible, but also I don’t care.

-

*[Jon L.] I’m not sure we’re talking about the same thing, but in Bill Rabe’s third (unpublished) Who’s Who & What’s What, Odgen Nash in response to inquiry had referred to himself as “a small ‘i’ irregular” -- because, I think, of his old friendship with Morley but casual (if that) relationship to Morley’s BSI. Nash was, Morley once said, one of the Doubleday, Doran “assembly men” present at the speakeasy in the East ’Fifties in 1930 when Morley was commissioned to write his “In Memoriam” foreword for the first Complete Sherlock Holmes. See Irregular Memories of the Early ‘Thirties, p. 19.

___________

I don’t know what Montgomery meant by that. He came into the BSI just as the “Adventures in Membership” system came into use in 1944, attending the annual dinner for the first time that year, and on pp.174-77 of Irregular Proceedings of the Mid ’Forties you’ll find his spring 1945 correspondence with Edgar W. Smith about an Adventure in Membership for him. His preference (since he felt others would have a senior claim on “The Hound of the Baskervilles” and “The Speckled Band”) was for “The Red Circle.” In those days before the Shillings, the elaborate Adventures in Membership certificates were produced by a member of Smith’s staff at General Motors Overseas Operations, on a none too brisk schedule. So Montgomery’s investiture wasn't announced until the 1949 dinner, when Irregular Shillings were in effect -- hence Peter Blau’s list of Irregular Honors giving that year for Montgomery. But back in 1945 Smith had gone ahead and told Montgomery, in a letter dated April 16th, that his preferred investiture “has now been formally assigned to you as your designated Adventure in Membership.” Since it was then nearly four years before its announcement in 1949, I wonder if Montgomery started distinguishing between two states of membership that way. Or maybe he thought of the Shilling as something more than denoting membership.

But I am wondering in saying this. Perhaps the matter can be cleared up when I get to the ’Fifties volumes of the Archival History, or perhaps Peter Blau or someone else can shed light on this.

[September 6, 2010]

Return to the Welcome page.

JOHN LEHMAN TELLS ME OFF (re: no. 7 below):

Dear Thucydides:

Your comments on the subject of bodice-ripping sent a shiver of dismay up my leg. You obviously are unaware of the prominent place ripping this garment has had in the advance of Western Literature. You are just the kind of author to introduce an Euclidian proof into an elopement.

For Shame!

All I can say to that is

Actually, Don Pollock and I once wrote about “Packaging Holmes for the Paperbacks” that way in Baker Street Miscellanea (No. 31, Autumn 1982). And then your old fellow saddle-tramp Lenore Carroll touched on the same thing in “Exploring ‘The Country of the Saints’: Arthur Conan Doyle as Western Writer” in BSM 51 (Autumn 1987). So it’s not like there’s no precedent, I admit.

[September 6, 2010]

Return to the Welcome page.

DAVID E. COTE: What is the history of Rex Stout and the BSI?

Rex Stout was well-known for his Nero Wolfe mysteries when in early January 1941 Irregular Lawrence Williams suggested to Edgar W. Smith that Stout would be a good person to attend the up-coming 1941 annual dinner (held the 31st) and respond to some awful things Somerset Maugham had said about the Sherlock Holmes stories in a recent Saturday Evening Post article. Stout accepted Smith’s commission, but did not carry it out. Instead he agitated the Irregulars that night with his soon notorious talk “Watson Was a Woman” (which included an acrostic in which titles of Watson’s tales spelled out the name Irene Watson).

But in not too much time, the Irregulars decided Stout’s heart was in the right place (after all, Archie Goodwin in at least one Nero Wolfe book had mentioned a picture of Sherlock Holmes hanging on the wall of their West 35th Street office), and he became a regular at the dinners; soon with a place at the head table, and the investiture “The Boscombe Valley Mystery” (conferred in 1949).

In 1954, the Higher Criticism of the Wolfe Canon got underway with an article in Harper’s Magazine (July) by editor Bernard DeVoto. He had already turned down an invitation from favorite-contributor Elmer Davis to join the Baker Street Irregulars, on grounds of silliness. But DeVoto did not feel Irregularity was silly in the case of his favorite detective stories, and in “Alias Nero Wolfe” (in his editorial “The Easy Chair” column in that month’s issue), he was even a bit harsh in the way he went about it:

According to a friend of mine who belongs to the Baker Street Irregulars [DeVoto began], a paper by one of his colleagues suggests that Nero Wolfe may be the son of Sherlock Holmes’s brother Mycroft. I cannot find the treatise that contains this absurdity and mention it only as an example of the frivolous speculation tricked out to look like scholarship with which the Holmes cult defrauds the reading public. In stating here the insoluble problem which will always frustrate biographers of Nero Wolfe I confine myself, as a member of the American Historical Association in good standing, to examining the source documents according to the approved methods of historical research. I construct only one hypothesis and I make no test of that one, leaving it for other scholars to test and apply as they may see fit.

DeVoto proceeded to spread frivolous speculation tricked out to look like scholarship across half a dozen pages in that month’s Harper’s, all for the purpose of confounding Irregular speculation about Nero Wolfe’s parentage. (DeVoto could be very dogmatic: see BSI Michael Dirda’s retrospective review of DeVoto’s enjoyable but dogmatic ’48 book of interest to Irregulars, The Hour: A Cocktail Manifesto.)

DeVoto’s volley only encouraged Irregular speculation, and the principal word on the subject, “Some Notes Relating to a Preliminary Investigation into the Paternity of Nero Wolfe,” was published in the Baker Street Journal in 1956 by John D. Clark, later “The Politician, the Lighthouse, and the Trained Cormorant,” BSI. (Included also in Philip Shreffler’s landmark anthology of BSJ scholarship, Sherlock Holmes by Gas-Lamp, 1989.) It answered DeVoto’s objections and deflections, and strengthened the case. The canny Stout refused to confirm or deny, but certainly abetted Clark’s case with the note he sent Clark about his investigations, printed in the article in facsimile.

DeVoto might as well have been King Canute commanding the tide not to come in. In 1969 William S. Baring-Gould, already the author of Sherlock Holmes of Baker Street and editor of The Annotated Sherlock Holmes, made the idea a foundation-stone of another book, Nero Wolfe of West 35th Street. And Nicholas Meyer (“A Fine Morocco Case,” BSI) made use of the idea as well in his novels.

Back in 1942, at that January’s BSI dinner, Julian Wolff had responded to Stout’s “Watson Was a Woman” with a talk of his own entitled “Nuts to Rex Stout.” Stout was not in attendance to hear it. A strident anti-isolationist before Pearl Harbor, he was off creating the Writers War Board to support the U.S. war effort. But when Edgar Smith sent him a copy of Julian’s paper, Stout was not chastened.

“I smile sardonically at Dr. Wolff’s involuntary (and pathetic) self-betrayal,” Stout replied to Smith on March 8, 1942: “I respect him for his loyalty to a lost cause, but what ineptitude! The poor chap! He labors for weeks to produce an acrostic which proclaims NUTS TO REX STOUT, and follows it with some observations upon a certain wound conclusively demonstrating that what the situation really demands is NUTS FOR DR. WATSON.”

But Julian Wolff was a big man in a small body. In 1961, when he became the BSI’s Commissionaire, he created the honor known as the Two-Shilling Award “for extraordinary devotion to the cause beyond the call of duty,” and the first one went that January to Rex Stout.

Besides Baring-Gould, well known to Irregulars is John McAleer’s biography Rex Stout in 1977. Less known, but worthy of attention, is David R. Anderson’s elegant study of the Nero Wolfe tales and their author, also titled Rex Stout (1984), in Frederick Ungar’s series of detective/suspense fiction studies. Anderson, a valued contributor to Baker Street Miscellanea when he was was a professor of English at Texas A&M and Denison Universities, is now president of St. Olaf College in Northfield, Minn.

[September 6, 2010]

Return to the Welcome page.

JOHN LEHMAN: Thank you for your reply on Woollcott vs the BSI as it were. [See no. 5 below.] I read [Woollcott’s posthumous collection] Long, Long Ago: in his essay “The Baker Street Irregulars” (can you sue the Woollcoott estate for plagiarizing your novel’s title, or is the “s” enough of a difference to get the wretches off?), and I never could and still can’t find anything in it to offend even the most prickly Sherlockian. Even the opening antidote about Abdul-Hamid the Damned was a tip of the hat to the Canon. The piece is a weak one by Woollcott’s standards, but he does drop the name of our buddy Logan Clendening. As a novelist, I’d sure insert “the Fabulous Monster” if I could find space for him. I suppose the Woollcott personality will remain more renowned than anything he wrote.

That’s right, and I didn’t exactly find space for Woollcott in Baker Street Irregular -- he storms up the stairs to Morley’s hideaway office on West 47th Street, flings open the door, marches in, and seizes control of the secret meeting going on between Morley, Elmer Davis, Edgar W. Smith, Fletcher Pratt, Rex Stout, and my protagonist Woody Hazelbaker. (Though Rex Stout soon seizes it away from him.)

I think I’ll leave the Woollcott Estate alone. You can’t copyright titles of books, and if you could, this one would belong to the Conan Doyle Estate;-- fortunately, my client in a different sphere of my Irregular life.

However, the sad lack of a good old-fashioned bodice ripping in the previews of Baker Street Irregular is a discouragement for further page turning.

If you keep complaining about this, people are going to wonder about you.

[September 5, 2010]

Return to the Welcome page.

SUSAN DAHLINGER: As we are nearing the 20th anniversary of women’s admittance to the Baker Street Irregulars, how much of a seismic shock rippled through the all-male societies when women began to appear at the BSI Dinner and what was the approximate attrition rate among the menfolk? How heavily attended are the all-male scion societies these days, setting aside the Pips, as it is not a scion society? Are they dying slowly or stronger than ever?

I don’t know that I’d call it seismic, exactly; though I wouldn’t call it joyous either. The all-male scion societies 20 years ago that occur to me were The Maiwand Jezails of Omaha, Hugo’s Companions of Chicago, Philadelphia’s Sons of the Copper Beeches, The Speckled Band of Boston, and The Six Napoleons of Baltimore. My experience of Hugo’s Companions is limited, and nil in the case of The Maiwand Jezails and Speckled Band, but none of them have changed their policies. Nor have The Six Napoleons nor The Copper Beeches. I’m a member of the latter, and also of Chicago’s Hounds of the Baskerville (sic), but while both have only male members, one sees many women at the Hounds’ sole annual gathering every autumn, and not only spouses but others invited on their own merits -- including you this year, or so I hear, Dahlinger. Taking place simultaneously with the Copper Beeches’ spring and autumn dinners every year is a dinner for wives called The Bitches of the Beeches -- started long ago by my late mother-in-law Jeanne Jewell, the idea being to get their drunk husbands home alive. (And a good idea, too.) Not that the Bitches dinners are the least bit teetotal either.

I suspect the attrition rate among men in these scions due to the change of policy by the BSI is close to zero, though it did affect the allegiance of some to the BSI itself. I couldn’t say how attendance at events has been affected, in some cases because I’ve never having participated in theirs, in others because what strikes me as the principal reason for smaller turn-out today compared to 20 years ago is the same demographic problem affecting the BSI, alluded to in the concluding chapter of my last “Certain Rites, and Also Certain Duties.” Of the seven new BSI investitures in 2008, I noted,

three went to “30-somethings,” the BSJ exulted, “[who] instantly lowered the median age of Irregulars significantly, in addition to helping ensure that there will be a new generation to take over the torch when it is passed.” Actually, it will take more than three “30-somethings” to lower the BSI’s median age significantly. The graying of Baker Street Irregularity has been a source of mounting concern during the past decade, and continues to be despite the new investitures, judging from the Editor’s Gas-Lamp in Autumn 2008’s BSJ: “we need to bring new faces, new members who are younger and more energetic, to our way of viewing the world. If we don’t, we risk seeing the end of organized Sherlockiana within the next twenty years.”

A prospect not to be scoffed at? It has been a long time since the “Junior Sherlockian movement” of the 1960s replenished the BSI’s ranks during the ’70s, and since the comparable “Sherlock Holmes boom” of the 1970s flowed from the successes of the Royal Shakespeare Company revival of William Gillette’s Sherlock Holmes and Nicholas Meyer’s novel The Seven-Per-Cent Solution. Even the wave of newcomers from the television series starring Jeremy Brett that debuted in 1984 was a long time ago now.

Ahem. I need to point out that the first woman to be an Irregular, mystery critic Lenore Glen Offord (“The Old Russian Woman”), was tapped way back in 1958, but I also acknowledge that it didn’t include invitations to the BSI’s annual dinners.

And now that women do have seats at the national table, why, in your view, have we seen so little classic Sherlockian scholarship from women or leadership at the scion level? So far, in the Manuscript and International Series published by the BSI, why am I not seeing women’s bylines more often, if at all?

That would be sheer conjecture on my part. It’s a question you’d have to address to ones directly responsible for those series of books published by the BSI, or to the Big Cheese himself, Mike Whelan, who has also presided over the International Series from the start, I believe.

Many scion societies today do have women at the helm, on the other hand, and not only recently founded scions. One of the earliest is San Francisco’s Scowrers & Molly Maguires, and while established in 1944 by men (San Francisco Chronicle columnists Anthony Boucher and Joseph Henry Jackson), and later chaired for many years by Old Irregular Robert Steele, today the office of The Bodymaster, Black Jack McGinty is held by the redoubtable Marilyn MacGregor (“V.V. 341”).

[September 2, 2010]

Return to the Welcome page.

JOHN LEHMAN: Did Alexander Woollcott really crash the BSI dinner, or come as an invited guest? From what I can tell the issue is unresolved. I don’t know if Woollcott had a history of party crashing or not.

Woollcott attended the first BSI annual dinner on December 7, 1934. He was of course a notorious enfant terrible, and I’m sure not above crashing a party given by a fellow book-caresser like Christopher Morley. But Vincent Starrett knew Woollcott was coming in advance (mentioning same in a letter to Frederic Dorr Steele asking him to attend as well, which Steele did -- November 23, 1934, text at my “Dear Starrett--”/“Dear Briggs--” page). In fact Starrett proceeded to Christ Cella’s by hansom cab that evening with Woollcott, from the latter’s apartment (known as “Wit’s End”) at 450 East 52nd Street.

The question is whether Woollcott was expected by Morley that night, or instead came as an unwelcome surprise to him. I think the burden of evidence indicates he was expected by Morley, despite Robert K. Leavitt’s expostulations to the contrary in his 1961 BSJ two-parter “The Origins of 221B Worship.” When Edgar W. Smith started organizing the 1940 revival dinner, Morley dug up an old invitation list for Smith’s use, and Woollcott was on it. (Reproduced in facsimile in my Disjecta Membra.) Woollcott had been crossed off (unclear when), but Woollcott had won few friends in the BSI with his December 29, 1934, New Yorker report on the first annual dinner -- “condescension,” Morley later referred to it.

I can’t swear that Smith invited Woollcott to the 1940 dinner, or subsequent ones prior to Woollcott’s death in January 1943. But he sent Woollcott a copy of his 1939 Appointment in Baker Street lavishly inscribed to Woollcott as Baker Street Irregular, and Woollcott appears on Smith’s December 5, 1940, BSI membership list given in my BSJ Christmas Annual “Entertainment and Fantasy”: The 1940 BSI Dinner. So I presume Woollcott had been invited to the January ’40 dinner at the Murray Hill Hotel too.

Woollcott appears in my forthcoming BSI historical novel. He has only one scene with a speaking part, and that in June 1940, but he was such a Fabulous Monster it was great fun to write him into the tale.

[September 2, 2010]

Return to the Welcome page.

ROBERT S. KATZ (he must think I have nothing to do in retirement but answer his questions. Well, I do owe him a few favors . . . .): It would certainly be worth hearing about the naming of Holmes Peak and the role Richard Warner played in the process.

The saga of the Holmes Peak will have to await another historian to do it and its Head Sherpa, the late Richard Warner, full justice, Bob. As you know, it’s been my steadfast intention from the start to cover the years 1930 to 1960, when Edgar Smith died and Julian Wolff succeeded him, and then stop, since the decades which followed are too recent for sound historical judgments. But in 1985, Dick Warner of Tulsa (“High Tor,” BSI) published his Guide Book and Instructions for the Ascent of Holmes Peak, and I reviewed it for Baker Street Miscellanea (BSM 43, Autumn 1985:

As if to prove that the age of Sherlockian fun is far from over, let us turn to 1985’s humorous highlight, Richard Warner’s guide to the ascent of Holmes Peak. Those acquainted with the doings of The Afghan Perceivers of Tulsa know well the daring of their intrepid exploits, which have struck awe (and some terror) in small towns throughout the American Southwest. But none have reached so high a pinnacle as the naming and ascent of Holmes Peak, which rises majestically 262 feet above the prairie floor, and from whose wind-swept summit practically all of Osage County, Oklahoma, can be seen. Warner has told elsewhere the tale of his ordeal to have this mountain named after Sherlock Holmes, particularly the struggle with Bishop Eusebius Beltran, Primate of the Catholic Diocese of Tulsa (which for a time co-owned the land in question), who in turning his cold and pale countenance against such frivolity declaimed that he sought a name “more meaningful to his work.”

But time and Warner prevailed, and in this little chapbook, with a foreword by Michael Hardwick who represented the Empire at the dedication of Holmes Peak, Warner relates all one needs to know in order to scale this lofty monument to the best and wisest man we have ever known. He provides the history of Holmes Peak, describes its geology (Holmes Peak is eroding and will disappear one day) and its flora and fauna (some snakes are poisonous, but all are aware of the dangers of attacking people who have read “The Speckled Band”); he gives directions to find Holmes Peak, describes the natives and local customs (B.Y.O.B.), and advises the prospective Sherlockian Alpinist on permits, medical attention, bearers, appropriate climbing equipment, and food (an Ascent Pack can be purchased from the Holmes Peak Preservation Society, including such local delicacies as poke green salad and squirrel stew.) Warner guides Irregular mountaineers through the harrowing four-stage ascent from the base camp to the summit (from which you can occasionally catch a glimpse of Bishop Eusebius B. burning copies of the Canon), dispensing along the way a few useful trail warnings (such as not molesting those piles of brown stuff along the path). He concludes by describing the Preservation Society’s elaborate future plans for Holmes Peak, including such juicy things-to-come as the Scenic Highway to the top, the Holmes Cenotaph (a design contest will be announced soon), the Doyle Ski Basin, and Holmesworld amusement park.

Buster Keaton could not do it better than the deadpan Warner, without whom Holmes Peak might never have been named (or even noticed). To have been at the dedication last summer, complete with the Afghanistan Perceivers’ widely dreaded drum-and-bugle corps, must have been a marvelous one-of-a-kind occasion; but much of its charm and wit is surely captured in this little chapbook.

. . . . John Lehman (“The Danite Band”), who was Avenging Angel of The Great Alkali Plainsmen of Greater Kansas City during Dick Warner’s heyday in the 1980s, offers this additional intelligence:

I certainly remember Holmes Peak. We even hiked to the top without oxygen and lived to tell the tale. At one time we had passes for the ski lift, but I have seem to have misplaced them (as Dick seemed to have misplaced the lift).

It is a lovely hill, what in the Ozarks would be called a “bald knob” (that means no trees, for the less botanically astute), and the view is very fine. When Bishop Eusebius Beltran told Dick that the hill needed a name “more meaningful to his work,” a lesser mortal would have taken no for an answer, and returned to whatever one does on a windswept prairie. Dick, however, cut out the middleman and wrote directly to the Pope.

Dick’s case, boiled down, was that as Sherlock Holmes was once employed by the Vatican, naming the Peak after him qualified as meaningful to the Bishop’s work. This letter was promptly bounced back to the esteemed Bishop Eusebius Beltran (fiction writers, I defy you to create a more dazzling cognomen), who replied on behalf of his Pontiff. Dick showed this document to John Bennett Shaw, who was an active member of the Knights of Columbus and other arms of the Church. John told Dick the good Bishop had expressed himself harshly as a Bishop was allowed to, and still stay on the side of the angels. (It was Dick’s contention that the smoke that occasionally rose from the Bishop's establishment was caused by copies of the Canon being burned. However, I don't know if any empirical research was done on this point.)

My memory slips on how the impasse was overcome. I think the property fell into other hands, but I could be wrong about this. However, the noble Peak was in the end named after the Best and Wisest Man we will ever know, and that must be accounted a happy ending. It proves that even Bishops may not always know on whose side the angels are.

Return to the Welcome page.

ROBERT S. KATZ: You commented on Bill Rabe in your reply to Julie’s question. Perhaps you could tell us a bit more about Bill and his role in BSI. It would be interesting to learn more about his Who’s Who, his role in the Voices of Baker Street, the formation of the Mrs. Hudson’s Breakfast, and his general conduct at BSI meetings.

Wilmer T. Rabe will get a chapter of his own in the first ‘Fifties volume of the Archival History, along with his Old Soldiers of Baker Street (the Old SOBs). After returning home from Europe, Bill went from the U.S. Army directly into the BSI at the beginning of the ‘50s, and by 1955 had the investiture of “Colonel Warburton’s Madness,” which also tells us Edgar W. Smith was a shrewd judge of men. Bill was an unforgettable personality with a zany streak of humor, and added something long-lasting to the BSI weekend in January with Mrs. Hudson’s Breakfast. Someone just the other day mentioned Bill referring, in a 1982 recording on Voices of Baker Street, to that year’s Breakfast as the twenty-ninth, which means the first one would have been in 1954.

I haven’t confirmed it yet, but it could have been even a year or two earlier. Bill’s 1961 and ’62 Sherlockian Who’s Who & What’s Whats have been of constant assistance to me, in researching the Archival History volumes to date, but I’ve also had the benefit of an unpublished third edition, compiled in 1968, but set aside by Bill when he left Detroit’s Wayne State University for a new role in life, director of publicity for the Grand Hotel on Mackinac Island, Michigan, “the Miami Beach of the North.” When I started the Archival History effort, Bill went up to his attic, found the four jumbo three-ring binders on which he’d arrayed the data for this third edition, and shipped them to me, God bless him. I consult them constantly.

Bill’s contributions to the BSI and our understanding of its history are legion, but his masterpiece is his splendid history of a piece of Irregular folklore bestowed upon the BSI at the end of the ’40s by its greatest musical voice, James Montgomery (“The Red Circle”) of Philadelphia’s Sons of the Copper Beeches: We Always Mention Aunt Clara. I find I reviewed this item myself in Baker Street Miscellanea when it came out in 1990, see here. And I also see that there is a signed copy of Bill Rabe’s book available on abebooks.com for a mere eight bucks, so anyone who doesn’t have it should stop reading this this very instant, and go grab it before somebody else does.

Bill’s papers for this work are in the University of Minnesota’s Sherlock Holmes Collections, and the finding aid at special.lib.umn.edu/findaid/xml/scrb0008.xml includes a biographical sketch shedding still more light on this bright and wonderful Irregular.

Return to the Welcome page.

Julie McKuras: I think we can all pretty well agree on who the most influential Sherlockians (leaving out Father Knox) of the 1930s and 1940s were; Starrett and Morley, and I'm sure others. The ’50s must belong to Edgar W. Smith and the ’60s to Julian Wolff, as the leaders of the BSI during those decades. Now that a perhaps adequate amount of time has gone by to reflect on what they accomplished, who else would you consider to have had the most influence in the ’50s and ’60s that shaped the organization? Besides the obvious Smith and Wolff, that is.

Good question. I have a tentative answer involving three men. Perhaps the most important during the 1950s and ’60s was William S. Baring-Gould. In the ’50s he overhauled the Canon’s chronology; in the early ’60s he used his 1955 chronology to structure a full-fledged biography of Sherlock Holmes of Baker Street; and in ’67 (the year he died) he produced his massive Annotated Sherlock Holmes based on his chronological ordering of the tales and subsequent biography. It not only had profound effects upon our scholarship’s trajectory, it brought huge numbers of new adherents into the fold (including me). ---- The second was John Bennett Shaw, for his significant expansion of the BSI’s constellation of scion societies. Not only for the number and the jubilant spirit he brought to the process, but also for the displacement of the BSI’s previous center of gravity in the Northeast. Not even Starrett in Chicago all those years did as much in this regard. (In addition, these two men, Baring-Gould and Shaw, also had a significant effect upon the BSI by being early advisers to the nascent Adventuresses of Sherlock Holmes in the 1960s, though some might wish that Baring-Gould had lived longer to maintain the gentility of his outlook, and offset the more mischievous streak in Shaw’s advice to ASH.) ---- And finally, I’d say Wilmer T. “Bill” Rabe, for his key role in expanding the BSI weekend’s scope. It already had the annual dinner and the Gillette Luncheon when he joined the growing throng in the early ’50s, and he added Mrs. Hudson’s Breakfast, a key step toward the BSI weekend being the Sherlockcon it is today. (What have I wrought, he might say if he were still with us; though perhaps he would only chuckle. Bill saw the humor in everything.)

But in the end none of these eclipse Julian Wolff’s influence from 1961 on. He not only presided over the BSI after Edgar W. Smith’s death, he also edited the Baker Street Journal for many years, influenced the BSI weekend’s shape with his Saturday cocktail party (first in his home for those he invited, then at the Grolier Club when numbers grew too great, and after that it was Katie bar the door); and then, Julian also handed out more investitures than anyone else before or since. Many of his Irregulars are gone today, like him, but lots of them made tremendous contributions to the BSI that are felt to this day.

Return to the Welcome page.

Robert S. Katz: Will Oursler’s talks at BSI dinners are said to be legendary, although I am not sure why. What can you tell us about him, his role in the BSI, and the nature of his presentation?

That would be the first question I’d get . . . .

Will Oursler was invested in the BSI in “The Abbey Grange” in 1956, preceded in that investiture by his father Fulton Oursler who’d received it in 1950. Fulton O. (died 1952), was a widely known writer, including of mysteries, with Will following in his footsteps. When I first attended the BSI annual dinner in 1973, he had been a fixture there many years, and I found it was a tradition for him to give one of the talks each year -- and for his talk to be totally unintelligible. Not just to me as a newcomer, but to everybody in the room. I’m not sure “legendary” is the word, but once you’d heard him, you didn’t forget it; they were incoherent, phantasmagoric, even delusional, but delivered in a sort of bravura style that held your attention. I remember sitting there my first time wondering what the hell, because I didn’t understand what was going on, but for others it was clearly an expected item on the bill of fare. I’m not sure that everyone enjoyed it, but Julian Wolff always seemed to: in part with a ringmaster’s satisfaction that the old boy had pulled it off once again, I think, and maybe also with a connoisseur’s appreciation of a performer living up to or even exceeding the year before. And for a few years, I had much the same reaction: “Here goes Will Oursler again, let’s see how wild it is this time, how’s he manage it year after year?” (This on the assumption that it was contrived. I don’t see how it could not have been, but that made you wonder how it got started the first couple of times, and I never heard an explanation; maybe someone else can tell us about that.)

Bill Vande Water has been engaged for some time in deep research on both Ourslers, for both the BSI and Mystery Writers of America, and if he ever finishes it, it should be the definitive account of the two men in our sphere.

Return to the Welcome page.