BIOGRAPHY AS LOCAL HISTORY

Catherine Cooke

© Catherine Cooke, 1997

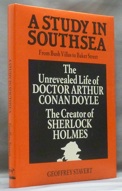

A Study in Southsea— From Bush Villas to Baker Street

by Geoffrey Stavert [1]

There has been a trend in recent years for biographies of Conan Doyle to concentrate on one aspect his life, examining his medical career, for example. or his interest in Spiritualism. In the year of Sherlock Holmes’ centenary, Geoffrey Stavert’s account of Conan Doyle’s life in Southsea appeared.

Stavert was well-qualified for the task. Originally from Westmoreland, he served in the Royal Artillery during World War II. Afterwards he served as an Instruction Officer in the Royal Navy. which took him to Portsmouth in 1957, where he settled. He retired from the Royal Navy in 1968, becoming Senior Lecturer in Communication at the Royal Military Academy, Sandhurst, finally retiring in 1984. He joined the Sherlock Holmes Society of London in 1975, serving as Joint Honorary Secretary for a number of years from the mid-1980s to the mid-1990s.

Stavert has long been “the Society’s man in Portsmouth,” lecturing to groups and showing visitors around the Doylean sites. One such visitor in the early 1980s was Dr. Alvin Rodin from America, conducting research for the book he was writing with Jack D. Key on Conan Doyle’s medical career. Stavert showed him Portsmouth and its Central Library where a collection of material on Conan Doyle is kept. Rodin remarked that Stavert was sitting on a major resource of which previous biographies had made little if any use, and asked why Stavert did not himself look into Conan Doyle’s time in Southsea. Stavert did, in his own phrase “haunting” the library and working through the back files of local papers page by page searching for accounts of Dr. Conan Doyle. Those papers which were not available in Portsmouth, The Hampshire Post and The Evening Mail, he consulted at the British Library Newspaper Library in Colindale.

It is true that previous biographers have paid scant attention to the Southsea years. Conan Doyle himself devoted some thirty pages of Memories and Adventures to the eight and a half years — less than 8% of the book — talking about his medical work, his home, marriage and family and his start in literature. He also briefly discussed some of the psychic studies he undertook at the time and gave a page each to his time with the Portsmouth Literary and Scientific Society and to his political work. Carr gives the period about 10% of his biography of Conan Doyle, Higham again about 10%, while Nordon gives it only four pages, about 2% of the biographical first half of his work (in the John Murray edition). Carr acknowledges the minute book of the Portsmouth Literary and Scientific Society; none seems to have delved any deeper into the local files.

Stavert’s book makes no claims to be a literary biography or an academic study of Conan Doyle’s life and work in Southsea. lndeed, when he started work Stavert envisaged publication as one of The Portsmouth Papers, a series of local studies written for the main part by local people covering old cinemas, breweries and such. As more material was uncovered and the work grew, Stavert approached Milestone Publications locally, who published it anticipating major sales in America — which did not materialize, perhaps due to the title’s use of Conan Doyle rather than Sherlock Holmes. The book fared far worse than it deserved. The first printing was 3,000, of which a third sold quickly before things slowed clown. The remainder were sold on to a second company, who went out of business.

That the book is primarily local history means that there are no detailed sources quoted. Stavert never regarded the work as an academic exercise, but did list “Sources and Acknowledgements,” which range from Conan Doyle’s autobiography and semi-autobiographical novels to the back files of newspapers held in Portsmouth Library, and includes several of the standard published works on Conan Doyle. Each chapter examines one year in strictly chronological order, giving any necessary context for any reference within the text At times it reads almost like a novel:

One fine day towards the end of June in the year 1882 a young man stepped ashore from a coastal steamer at Clarence Pier, at the western end of Southsea Common. He was tall, broad-shouldered, with plump cheeks, a well-developed moustache, and a pair of sharp, bold eyes which hinted that although it was only a month after his twenty-third birthday he had already been around a bit and could look after himself nicely, thank you.

While this makes for a very approachable and easy to read biography for the layman. the serious student of Conan Doyle usually feels happier with an attributed source for each assertion.

Being written for the more popular end of the biography market and for those who actually live in Southsea does mean that the book is extremely well illustrated. There are admittedly few of Conan Doyle himself (but those are uncommon: outside Bush Villas and on his bicycle), plus some illustrations for his work. There is, however, a wealth of background material hard to find anywhere else, ranging from views of the town Conan Doyle knew and the streets where he lived and worked, period maps, and advertisements, to the damage sustained during the bombing raids of 1939-45. Where period photographs are not available for a significant site, a modern photograph is used, with any later alterations noted. (The book is, in academic terms [if that is not too unfair], let down by its index. Coverage is only given to major references, and that not very accurately or consistently. In an academic book such an index would be sloppy; here it may have been dictated by economics or a wish not to put off prospective purchasers by making the book seem too “heavy.”) The strictly chronological approach coupled with the lack of references makes the work difficult for the serious researcher to use. An instance of this is Stavert’s discovery that Conan Doyle played football under the pseudonym A. C. Smith.

Consider that goalkeeper for a moment. The name Smith does not tell us anything, but is there not something familiar about those initials? Could they perhaps stand for Arthur Conan Smith? They undoubtedly did! Whether Dr. Doyle felt that, whereas cricket was a gentleman’s game in which he might very properly appear under his own name, the somewhat cloth-cap image of soccer might be off-putting to some of his lady patients, or whether it was just his own private little joke, we do not know.

For the next 40-odd pages Smith’s career is charted, but the identification with Conan Doyle seems to remain surmise. Only on page 103 do we read, “General Harward . . . made an appropriate speech mentioning many of the players by name, and of course gave the game away by referring to Smith throughout as Doyle.” Finally on page 140 we have actual published sources, “The Evening News reported A. C. Smith in his usual position at back, but the Hampshire Telegraph identified him as Dr. A. C. Doyle.”

Stavert himself questions whether newspapers can properly be regarded as primary sources, being all too prone to twist facts to suit headlines or just plain get it wrong. With that caveat coupled to the fact that the Conan Doyle family archives are still unavailable for scholars, there is little alternative for the would-be biographer than to turn to local history collections in the search for new facts about Conan Doyle. Scanning every page of every local paper for hours, days, even years on end, hovers between the tedious and the frustrating, particularly where microfilm is all there is to work with, and anyone who is willing to undertake it is much to be commended. It is inevitable, working in relative isolation like this, that some matters will remain speculation, interesting possibilities for future scholars to take further if opportunity presents itself.

The final chapter of Stavert’s work provides a good instance, when he looks at Conan Doyle’s brief return to Southsea in 1896, an interlude ignored by other biographers. Speaking of Conan Doyle’s second wife, he writes:

if we turn again to the Southsea guest lists for the summer of 1896, we find that in the weeks ending 2 May, 9 May and 16 May a Mrs and Miss Leckie were staying at the Grosvenor Hotel. The red-brick Grosvenor, at which both Boulnois and Conan Doyle had been dined out, stood less than a couple of hundred yards away from the Southsea Terrace across a corner of the Common.

Stavert does not push the point; he agrees it is no more than an interesting possibility that cannot be proved, that, if this is the same Miss Leckie, Conan Doyle may have met his second as well as his first wife in Southsea. How can such a point be proved or disproved, except by reference to private family papers or knowledge? Carr, who had access to both, states categorically, “Under what circumstances they met we do not know; but the date, which neither Jean Leckie nor Conan Doyle ever forgot, was March 15th, 1897. It was just a few months short of his thirty-eighth birthday. They fell in love immediately, desperately, and for all time.” Carr gives no actual source, but it is known that Conan Doyle wrote to his mother on the subject in the spring of 1897. Can we accept Carr’s word, or is there here another point for which we must await access to the family papers?

This isolationist approach does give rise to some surprising silences. Charles Doyle receives only two mentions. The first is at the end of 1883, where the death of Richard Doyle is mentioned a long with Charles Doyle’s increasing alcoholism, “perhaps complicated by the beginnings of epilepsy.” Stavert notes that “he was facing confinement in an institution.” The same paragraph is also the only mention in the entire book of Dr. Bryan Charles Waller, as he moves to West Yorkshire and offers Mary Doyle the use of a cottage rent-free. The chapter ends enigmatically, “So the Edinburgh home was breaking up. . . . It would mean financial security, yes. But at what cost?” There is no further discussion of arrangements at Masongill, of Waller, or of the circumstances surrounding Charles Doyle’s committal. The matter is one on which nearly all the biographies are reticent, largely of course due to the absence of hard evidence, the only in-depth treatment being by Michael Baker in The Doyle Diary. Charles Doyle’s second appearance, when he illustrates the book edition of A Study in Scarlet, is more interesting, Stavert speculating as to whether it was the plea of an abandoned father to his son: “Here I am — it is your father, still in being . . . ?”

More research, a little bit wider, would have increased the work’s value. Stavert briefly discusses the famous 1889 dinner at the Langham Hotel in London during these years, but states with respect to Gill, “Nobody seems very sure as to what the MP’s part in the meeting was —perhaps he was just brought in by Stoddart as a fellow Irishman and as an entertaining conversationalist.” In fact Thomas Patrick Gill, who was an Irish Nationalist, and MP for South London from 1885 to 1892, had been editor of the North American Review from 1883 to 1885. Though he has now faded from memory, he seemed at the time to have made a start on a promising literary career, and as such not such an unlikely fourth at this dinner. Indeed, one cannot help but wonder at the conversation of a Liberal Unionist of Irish descent like Conan Doyle, and an Irish Nationalist like Gill — if the scarcely less Irish Oscar Wilde let them get a word in at all that night!

The Southsea years were important ones for Conan Doyle — he was setting up in practice on his own for the first time, starting to make headway in his literary avocation, and, having met Louisa Hawkins, setting up as a family man. He was coming to prominence in the professional life and contributing to the social and sporting life of the town. Not surprisingly, much of this is mirrored in the local newspapers and in the accounts available of the Portsmouth Literary and Scientific Society. Stavert treats all of these in some detail.

The accounts of Conan Doyle’s setting up in medical practice arc attributed largely to Memories and Adventures and to The Stark Munro Letters. Using even admittedly autobiographical fiction as a source for biography is always a trifle tricky. Where does the autobiography stop and the fiction begin is a question that may come to mind here, as Stavert cites Dr. Doyle’s intervention in a wife-beating episode, quoting Stark Munro’s descriptions of the scene. Any doubts the reader may have as to the veracity of the episode are only laid to rest at the end of the book when Stavert describes the events at the dinner given in farewell as Conan Doyle and his family leave Southsea, where Conan Doyle tells the story in his speech.

Stavert’s treatment of fiction as autobiography is much clearer than that of some of the other biographers, prone to stating fiction as definite fact: the short story “His First Operation” has, for example, been cited with the definite statement that Bell was the professor and Conan Doyle the fainting student. Stavert’s extensive local knowledge allows him to track the fictional account through the very streets where they were claimed to have occurred, demonstrating at least Conan Doyle’s attention to detail and use of precise locations to add verisimilitude to his work. He also draws parallels between the factual accounts and the fictional counterparts wherever possible, such as the identification of 1, Oakley Villas, Birchespool, from The Stark Munro Letters, with 1, Bush Villas, quoting passages from the novel and the evidence of the 1881 Census records. Bringing in newspaper accounts of accidents and daily happenings in Southsea, Stavert evokes the world in which Conan Doyle lived and one or two of his early cases. Riding and carriage accidents, domestic violence and local crimes, all feature.

A consistent theme throughout the biography is that of Conan Doyle’s sources for his fiction. People with familiar names such as Chief Inspector Sherlock of B division, and Mr. William Henderson Starr, locum for Dr. Lysander Maybury, are noted in passing and identified in Conan Doyle’s stories. We read of Surgeon-Colonel A. F. Preston, severely wounded while serving with the Berkshires at the Battle of Maiwand. Some of Conan Doyle’s friends are more significant and given greater discussion. Dr. James Watson is a well-known instance, but Stavert also draws attention to General Drayson and his influence on the character of Moriarty, and to Percy Boulnois’ lecture on money. including the subject of the Bimetallic Question, dear to the heart of Mycroft Holmes.

There are some conclusions here again which could have been drawn had Stavert looked outside Southsea. Percy Boulnois was the Borough Engineer, but his family had connections with the Baker Street Bazaar, and it has been asked whether this influenced Sherlock Holmes’ choice of residence. As Conan Doyle’s practice grew, so did his household. Richard Lancelyn Green has wondered whether Innes Doyle’s coming to live with his older brother was the inspiration for the pairing of Dr. Watson and Sherlock Holmes. lf so, might not the housekeeper to whom Conan Doyle let his basement flat, the Miss Williams of The Stark Munro Letters, described as “a kindly old Scotchwoman who had been a servant to the family and was a mother to him and his little brother,” be the inspiration for Mrs. Hudson? It is a point Stavert does not make, though he does discuss briefly the major influences on Holmes and Watson. If, in a literary sense, Holmes grew up in London, he was born in Southsea, and we might expect some detailed discussion of possible influences on him. In fact, Stavert seems to accept without question Joe Bell as sole inspiration for Holmes, while sketching a more complex derivation for Watson. Much of Conan Doyle himself is there, be feels. Local Southsea lore, little-known elsewhere, attributes the character to Dr. James Watson, a rumor the doctor himself seems to have started; Stavert is not convinced.

One of Stavert’s richest sources were the accounts of the Portsmouth Literary and Scientific Society. Though referenced by other biographers such as Carr, Stavert was the first and indeed only biographer to date to make heavy use of them. Stavert sketches the Society’s history, remarking that the actual manuscript minutes are not very helpful, being merely “written to a brief, one-page formula.” One page is actually reproduced, signed by James Watson as President for the year of 1890, merely giving details such as the date, speaker, title of the lecture, number attending, and who took part in the discussion; nothing of what was said. The valuable material is the newspaper reports, added by “some thoughtful archivist.” From these, Stavert describes meetings and often Conan Doyle’s own contributions from 1883 on, noting for instance in some detail his first lecture in December of that year on “The Arctic Seas.” Stavert leaves us in no doubt of the importance of the Society to Conan Doyle’s social and professional development. Through it he gained experience of public speaking, a vast amount of out of the way knowledge, and a wide variety of social contacts, becoming joint Secretary of the Literary and Scientific Society himself in October 1886.

The Society was also to give Conan Doyle his first experiences with psychic matters, which he was investigating as early as 1887. Stavert devotes some time to this somewhat contentious subject. As is generally known, Drayson invited him to seances and table-turning experiments, but Stavert also identifies for the first time others in the area with whom Conan Doyle collaborated, most notably Arthur Vernon Ford and his family. Interestingly, Stavert quotes at length the letter published in the Evening News of May 9th 1889 from “Spiritualist,” in which the writer argues for Spiritualism to be accepted as “the strongest ally of a broad and enlightened Christianity.” Stavert believes this letter to be from Conan Doyle, and as such, if this be true, proof that his commitment to the cause dates back far earlier than many think. He puts his case well, though allowing counterarguments for the reader to make up his own mind on a point which cannot at this time be proven one way or the other. Stavert’s case might have been bolstered a bit had he also cited the pro-Spiritualist aspects of The Mystery of Cloomber, published in the same year and which he had discussed only twenty pages earlier.

Stavert did not set out to write a literary or academic biography, and it did not occur to him at the time to approach Dame Jean Conan Doyle for her input. He was not trying to probe Conan Doyle’s psyche or make any particular point about him and there is nothing contentious about the result. To Stavert, Conan Doyle was a genial chap, a popular man, above all story-teller, a judgment of which Conan Doyle himself would probably not have disapproved. While there are frequent references to Conan Doyle’s fictional works throughout the book, they are chronological events, research for or publication of a novel, or references to his life or to people he met. No attempt is made to assess their merit or to place them anywhere on a scale from popular fiction to literature. In that sense, Stavert lets Conan Doyle’s work speak for itself to readers who follow his not infrequent exhortations to read some of Conan Doyle’s lesser-known short stories and novels.

A Study in Southsea is the fruit of many years’ research, and raises many new lines of enquiry for scholars. It may be local history, geared as much if not more to the residents of Southsea as to the Doylean. That in no way diminishes its importance, and devotees of Conan Doyle will surely appreciate the skill with which he depicts the world in which Conan Doyle first made his mark. What Stavert has done is to present his reader with the fullest and most accurate account we have to date of Conan Doyle’s years in Southsea. Though slighter and far less academic, he has done for this period what Owen Dudley Edwards did for the Edinburgh years. Stavert has provided us with solid groundwork. Any widening of the scope and greater discussion of Conan Doyle’s life and work outside Southsea would have detracted from the local nature of the book and thus have been opposed to what Stavert was setting out to do. He leaves it for others to take the work further, discussing the import of the discoveries in the context of our knowledge as it stands, and, more importantly, in the light of the new material which, it is hoped, will one day become available again.

NOTES

[1] Portsmouth, Hants.: Milestone Publications, 1987.

Editor’s Note

Catherine Cooke (“The Book of Life,” BSI) lives in Wimbledon, England, is an executive in London’s Westminster City Council and library system, and has long been one of the gears making the Sherlock Holmes Society of London function. She is also the curator of the Marylebone Library’s Conan Doyle Collection.