RICHARD HUGHES AND THE BARITSU CHAPTER

Recently I had occasion, for the Friends of the Sherlock Holmes Collections’ newsletter’s editor, Julie McKuras BSI, and for her contributor to an issue, Mitch Higurashi BSI, to pull out the item below that I’d done originally as my 1996 paper for The Five Orange Pips, and later had turned into the “Third Scionic Interpolation” in Irregular Crises of the Late ’Forties, in ch. 7, it being a remarkable sidelight on BSI history.

I met Richard Hughes only once, when he came to Washington D.C. in the late 1970s on a book tour. He was an Australian who’d become virtually the dean of the foreign correspondent corps in East Asia, based in Hong Kong and before that in Tokyo. I had originally gotten in touch with him when I saw an essay of his in 1974, in the Far Eastern Economic Review, entitled “Confucius, Lin Piao — and Sherlock Holmes,” in order to reprint it in Baker Street Miscellanea. He readily gave permission for that, and in the correspondence that followed, made me a member of The Baritsu Chapter, the BSI scion society (really a society of its own) that he had co-founded in Tokyo in 1948.

After providing the piece below to Julie and Mitch, I acquired from a used books dealer in Sydney the biography of Richard Hughes that had been published there in 1982, two years before his death in 1984 at the age of 78. Some notes about Hughes’ Sherlockian experience from this book follow the piece below.

THE BARITSU CHAPTER

OF THE BSI

First notice of a Far Eastern scion society of the BSI appeared in Vincent Starrett’s Chicago Tribune column of September 14, 1947. “Walter Simmons, the Tribune’s correspondent in the far east,” it said, “writes that plans are underway to establish a far east chapter, of which more anon.” Anon turned out to be an entire year, but it did happen, the fullest account being provided long afterward in Foreign Devil: Thirty Years of Reporting in the Far East (Andre Deutsch, 1972), the memoirs of a larger-than-life Australian journalist and Sherlockian named Richard Hughes:

One of the cultural highlights of the Japanese Occupation, indeed, was the foundation, in 1948, of a still-flourishing Tokyo Chapter of the Baker Street Irregulars by Japanese, British, American, Australian and New Zealand students of Sherlock Holmes.

The historic founding meeting of The Baritsu Chapter of the Baker Street Irregulars was held at the Shibuya residence of Walter Simmons, Far Eastern representative of the Chicago Tribune, on 12 October 1948. Nine of the original twenty-five members have since been called to their reward; others have received honour and preferment in their varied callings; one has been knighted; but all survivors — and later members — although since widely scattered, maintain irregular but affectionate contact, and still rejoice in the good fortune of having been able to participate in the founding of the first and only Far Eastern Sherlock Holmes society.

It was unanimously agreed the society should be named The Baritsu Chapter, in reverent reference to the use — rather misuse, as later established by the Chapter — of that word by Holmes in The Adventure of the Empty House when, explaining his return from the dead, he credited his escape from Professor Moriarty to his knowledge of “baritsu, or the Japanese system of wrestling,” which enabled him to hurl the master criminal to destruction in the Reichenbach Fall.

The business of the initial meeting, after a hearty eleven-course Japanese banquet (with suitable quotes on the menu from the Holmes saga for each course), accompanied by an admirable Imperial Nada saké, comprised: (i) Election of a Chief Banto; (ii) The reading by Kenichi Yoshida of a scholarly paper, elucidating a long-standing Holmes mystery, prepared by Yoshida-san’s eminent grandfather, the elder statesman, Count Makino (prevented by illness from attending); (iii) A well-reasoned solution of the mystery of Hideki Tojo’s suicide attempt, advanced by the late General’s leading defence counsel at the war crimes trial, Dr George Blewett; (iv) a firsthand inside account of the detection and arrest of the mass-murderer, Sadamichi Hirasawa, for the poisoning of sixteen bank employees, by his tracker, Detective Tamigoro Igii of Tokyo homicide.

In addition to Count Makino, another notable absence from this initial meeting was Prime Minister Shigeru Yoshida, who pleaded urgent cabinet business and an appointment with General Douglas MacArthur, Supreme Commander, as reasons for a last minute cancellation of his attendance. A motion by Colonel Compton Pakenham that the honourable member’s explanation should be rejected as “inconclusive, inadequate, unsatisfactory and unsatisfying” was withdrawn, under pressure, following assurances by the Prime Minister’s son that his father would attend the next meeting — “at the expense of any possible governmental or Occupation crises.” (A pledge which was faithfully and happily kept.)

The Chief Banto elected that night was Richard Hughes, who continued to rollick in the role until his death in 1984. By then, perhaps the rest of the 25 original members had also been called to their reward. But The Baritsu Chapter continued to grow, and lives on today at least in the hearts of some, for Hughes over the years made many deserving individuals (even some undeserving, such as this series’s editor) members of the society.

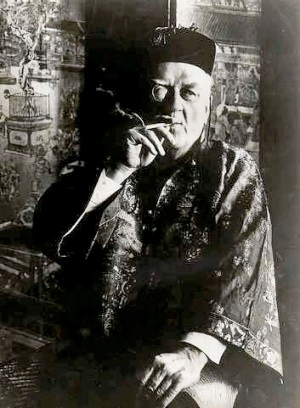

But in truth, the expansive Hughes became The Baritsu Chapter, during those first years in Tokyo, and later, for the remainder of his life, in Hong Kong. Well before its founding in 1948, he had been using the pen name of “Dr. Watson, Jnr.” to sign mystery book reviews for the Australian press, and a 1944 collection of Australian true-crime accounts, Dr. Watson’s Case Book: Studies in Mystery and Crime (dedicated “in reverent and humble tribute to The Master, Sherlock Holmes”). There were not many others before whom Dick Hughes was humble. Decades of covering war and peace in the Far East made him acquainted with the great men and villains of many nations. He had sparred with all of them without ever giving an inch, while living life to the fullest. When he died, at the age of 78, his lengthy obituary in the Far Eastern Economic Review said that:

The huge colourful Falstaffian figure of Richard Hughes — otherwise known as Dick, or “The Archbishop” — finally succumbed to the battering to which its owner had subjected it for more than five decades.... Falstaff reborn, a man-mountain of wit and magnanimity, of Shakespearean eloquence and Rabelaisian humour, at home in the company of the kingly and the very common.

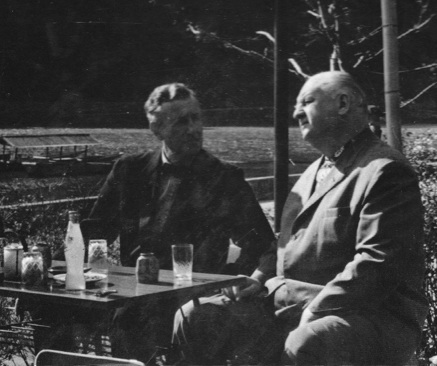

Hughes swaggered across the landscape of the Far East, and his London Sunday Times editor, the novelist Ian Fleming, gave a vivid account in his 1964 book Thrilling Cities of what it was like to have Dick Hughes for a guide on a “business” trip to Hong Kong, Macao, and Tokyo. “On my first evening he and I went out on the town,” said Fleming, starting at “the solidest bar in Hong Kong, the meeting place of Alcoholics Anonymous,” and then on to a Chinese dinner where Hughes “spiced our banquet with the underground and underworld gossip of the colony,” including why Japanese mistresses are preferable to Chinese girls, how to treat servants in the Orient, and the Suzie Wong class in Hong Kong. In Macao, Hughes introduced Fleming to the syndicate that ran the vice there, took him to the “very best” brothel in town, and there taught him how to lose at fan-tan, while telling the girls’ fortunes. In Tokyo, Hughes continued Fleming’s education with the pleasures of the Japanese bath, raw fish, and limitless saké, soothsaying Japanese-style, the geisha in theory and practice, and the perils of crossing the International Date Line (as Fleming was about to do) and finding yourself on Friday the 13th two days in a row.

Ian Fleming, left, with Richard Hughes.

Fleming made Hughes a character in his last James Bond novel, You Only Live Twice — Dikko Henderson of the Australian Secret Service, whose opening remark to James Bond is: “Now listen, you stupid limey bastard.” It was an unusual distinction for Hughes to become a character in one of John Le Carré’s spy novels as well, The Honourable Schoolboy — Old Kraw, of MI6. Taking on of SPECTRE and SMERSH seemed very fitting for Hughes. After his death, the Far Eastern Economic Review said of this affable and gregarious man, that he “reserved his anger for communists.... one knew when Hughes had hoisted aboard sufficient vodka, when he would propose a toast: ‘Death to the Commie Dogs!’”

So it came as a surprise to many people when they learned, some years after his death, that from the 1950s on, Richard Hughes had been an agent of the Soviet KGB.

And it came as a great surprise to the KGB, no doubt, to learn that in fact Hughes had been not theirs, but a British double-agent actually working for MI6, and feeding the KGB disinformation all those years. When the KGB had approached to recruit him as a spy, he had contacted Ian Fleming, who had been in MI6 during the war. In a short time, Hughes had received instructions to accept the KGB’s offer (but to demand double, so it would take him seriously), and pass along the data that MI6 would provide from time to time.

Richard Hughes, Chief Banto of The Baritsu Chapter, Far Eastern scion society of the BSI, did so for years. The codename he chose for himself in this double-agent work on behalf of Her Majesty’s Government was ALTAMONT.

Notes on Richard Hughes from The Man Who Read the East Wind:

A biography of Richard Hughes, by Norman Macswan

(Kenthurst, N.S.W.: Kangaroo Press, 1984):

As a schoolboy, “On the long walk back home, Hughes would make up stories for the other boys and tell them of the latest adventures of Sherlock Holmes. His father had started him on Conan Doyle’s hero and his love for the sardonic Holmes was to grow stronger over the years. (To this day he can identify virtually every character in every Holmes book and will not concede that Holmes died but that he lives on his bee farm in Sussex. ‘If he died The Times would have announced it,’ he still claims indignantly.” (p. 13)

In November 1920, when Hughes was sixteen, “Conan Doyle came to Australia to lecture on spiritualism and Hughes’ father was involved in the arrangements for the visit. To his intense delight, Hughes was entrusted to pick up Conan Doyle from his hotel and take him in the family Oakland to the theatre where the great man was to lecture. Young Hughes told the author how he used to tell his school mates some of the Sherlock Holmes stories. Conan Doyle merely smiled. ‘He wasn’t very forthcoming,’ Hughes would recall forlornly in later years. Doyle’s primary interest at the time appeared to have moved away from Holmes.” (p. 22)

In his first newspaper job, in 1936, “One of his chores was to review mystery stories and he assumed the by-line ‘Dr Watson, Jnr’. When there was a dearth of mystery stories he would make them up and review imaginary books, much to the bewilderment of Sydney booksellers. He used the pseudonym ‘Pakenham’ for these reviews.” (p. 25)

In 1939, with a mysterious disappearance in New Zealand in the news, his editor, “in a frivolous mood, said to Hughes: ‘Dr Watson, Junior, you’re a great authority on crime. Why don’t you go over to New Zealand and solve this mystery for us?’ Hughes replied: ‘Certainly. I’d be delighted.’” He did so, and came to conclusions contrary to those of the police, and wrote the news story “in true Sherlock Holmes style” — and was soon proven correct. (pp. 28-30)

In early 1944, while a war correspondent, “Hughes brought out his first book, a modest little volume called Dr Watson’s Casebook: [Studies in Australian Crime], which dealt with some of the great mysteries of the world. The pseudonym was Dr Watson Jnr and he dedicated it ‘in reverent and humble tribute to the master, Sherlock Holmes, the greatest and the wisest man I have ever known.’” (p. 58)

After the war ended, Hughes was assigned to Tokyo, where his “lifelong love of Sherlock Holmes reached some sort of fulfillment in 1948 when he and other aficionados formed a Tokyo chapter of the Baker Street Irregulars. They called it the Baritsu Chapter. . . . Hughes was elected Chief Banto of the Chapter. . . . Walter Simmons, the Far Eastern representative of the Chicago Tribune, and one of Hughes’ greatest friends, hosted the first historic lunch,” and so on about The Baritsu Chapter’s adventures, drawn from the chapter about it in Hughes’ 1972 book Foreign Devil: Thirty Years of Reporting from the Far East. (pp. 70-72)

And there is more in the book, including Hughes’ anger at Communist Chinese attacks upon the Sherlock Holmes stories, some back-and-forth with Adrian Conan Doyle over whether Sir Arthur was Sherlock Holmes himself or not, Sir Arthur’s spiritualism, Sherlock Holmes as one of Hughes’ favorite “cultural disputation” topics over the several decades he was stationed in Hong Kong (he’d have loudly approved of Robert G. Harris’s Irregular encouragement of “confrontation, disputation, and dialectical hullabaloo”), and, tellingly for what was revealed some years after Hughes’ death about his life as a double-agent for MI6, the following when meeting with friends back in Melbourne:

One friend tested his knowledge [of the Canon] by quoting from the first paragraph in Conan Doyle’s His Last Bow: “It was nine o’clock at night upon the second of August — the most terrible August in the history of the world.”

Hughes delightedly quoted the final few words, spoken after Sherlock Holmes had revealed himself to surprised readers as the counter-spy Altamont who had outwitted the German Von Bork — “the most astute secret service man in Europe.” It was one of Hughes’ favourite Holmes stories. “There’s an East Wind coming — such a wind as never blew on England yet . . .,” he quoted correctly.

But, the biography continues, this was not an unusual accomplishment for Hughes: “His friends tried him on other Sherlock Holmes stories. Each time he showed his encyclopaedic knowledge of the character he steadfastly maintained still lived.”